Self-driving vehicles are incredibly exciting. Imagine how family road trips and commutes might change. Think of all the time you could get back if you didn’t need to be focused on the road. As a 7-year (recovering) consultant who is often guilty of consultant-speak, I know the value of “giving time back”. Not to mention the improved safety, lower cost, and lighter traffic. Self-driving would bring us one step closer to living like the Jetsons. At some point soon, most of the population might never drive a car.

Sounds amazing, right? The US military thought so too, so they launched a first-of-its-kind program in 2004 to attack the problem — by hosting a race.

The United States’ DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) set-up the race, which was hosted in the Mojave Desert near the California-Nevada border. They called it the DARPA Grand Challenge, and teams from around the country signed up to compete, racing cars that drove themselves. Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, and Caltech were among the teams that came together. The course was 150 miles, and 15 cars qualified. The stakes? $1M.

That year, nobody finished the course, no winner was declared, and the furthest car (from Carnegie Mellon’s Red Team) only made it 7 miles. Everyone was disappointed, but self-driving is a hard problem! And over the span of a few dusty hours, DARPA and the competitors spurred a ton of interest and enthusiasm for the space. They would run the challenge again in 2005, this time upping the purse to $2M!

The second time around, five teams completed the desert course. Here’s a photo of the winning car from Stanford’s team (nicknamed “Stanley”), and its race leader:

The guy with the medal – that’s Sebastian Thrun. After the competition, while on sabbatical from teaching at Stanford, he launched a self-driving project for Google in 2009. It eventually got named Waymo.

In the years that followed those first desert races, other participants launched their own autonomous vehicle (AV) startups. And most of them worked at Waymo first.

Zoox: self-driving car company founded in 2014 by Tim Kentley-Klay and Jesse Levinson. Levinson was on Thrun’s DARPA challenge team in 2007, and Kentley-Klay was on another team that same year. Amazon bought them in 2020.

Otto: autonomous trucking company founded in 2016 by Anthony Levandowski (remember him from Showtime’s “Super Pumped”?). He was a founding member of Google’s Waymo team, and Uber bought Otto six months after it launched.

Argo AI: self-driving car company founded in 2016 by Bryan Salesky. He was on the Waymo team from 2013-2016 and participated in the Urban Challenge. Argo was backed by Ford and VW in 2019.

Last, but certainly not least, was Nuro.

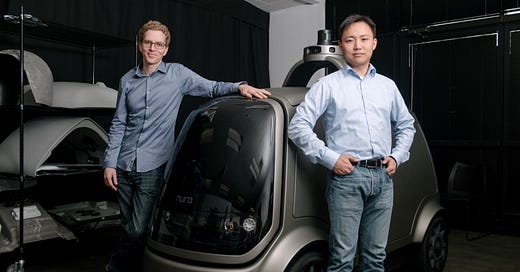

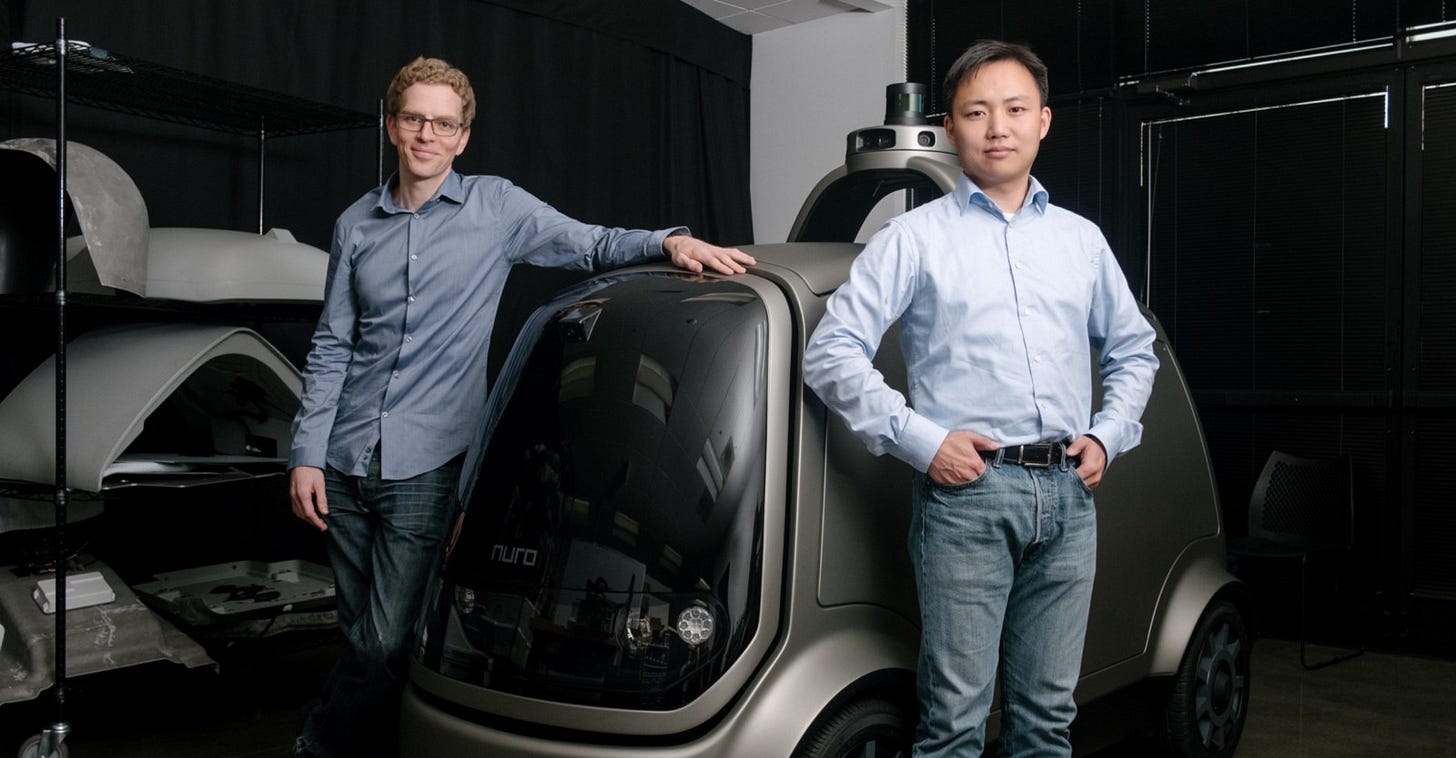

How did they differentiate themselves? Instead of chasing Otto into trucks, Nuro went in the opposite direction and focused on smaller cars. By limiting the footprint, they could maximize turn radius and have a greater margin of safety around the car. Beyond the physics, they also thought about situations where driving is a chore and not a pleasure. This would help them deliver on their vision of making everyday life better through robotics. Short, time-sensitive errands to pick things up stuck out as the opportunity. So they landed on a vehicle that acts like a futuristic grocery delivery pod. And by “they” I mean Dave (left) and JZ (right). Here they are with their delivery-pod-baby:

Dave Ferguson and Jiajun Zhu (JZ) are the dynamic duo that founded Nuro in 2016. They’re both deeply technical, and they met while working together at Google. I’ll give you one guess about which Google team. After having checked the box on DARPA (Dave) and Waymo (both), they saw their chance and went for it.

Dave and JZ both had serious experience on the core tech that makes AVs work (localization, perception, object classification, etc.), so they battled over who should lead the company… but not in the way you’d expect. To hear Dave tell the story, neither one necessarily wanted to be CEO, and they pitched each other essentially saying “no, you should probably do it.” Eventually, they settled on JZ as CEO, and Dave as the unofficial-spokesperson-co-founder. Which is great for us. Dave was born in New Zealand and the accent makes all his answers should brilliant. So imagine him reading his own quote:

“We thought ‘here’s an opportunity’… and we almost felt a responsibility to go after it, given where we were [at Waymo] and all the advantages we had.”

Today, they’ve already released two versions – the R1 and R2 – and the latest 3rd one is even better. Signaling flagship product status, they ditched R3 and named it “Nuro”. It has room for 500 pounds of cargo, is fully electric, and has customizable compartments for, hot, cold, or room temperature deliveries.

Because the Nuro doesn’t carry passengers, it completely changes the safety profile of the car. According to a study by the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI), any crashes the vehicle gets in will be 58% less dangerous to all parties involved. Because of that emphasis on safety, Nuro has recently made huge strides with regulators. After three years negotiating, in 2020 they were granted an exception from the NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). They can now operate their AVs without a few standard car safety features. There’s no need for windshields and a rear-view mirror if there’s nobody in there! They’ve also gotten all the necessary permits from California to run an autonomous delivery service.

If you’re asking yourself how to invest, you’re not the first. They’ve raised $2.1B at a valuation of $8.6B. Now they just need a fleet of cars and some hungry customers.

What are investors seeing that has them so excited? Big bets with strong odds.

Bet #1 – Limiting scope to make the AI problem easier

As we’ve already talked about, this is key. Most of the AI we use daily is narrow, not wide. Here are two examples of what I mean:

Netflix uses AI to recommend movies to you based on what you’ve watched and what other people are watching. But it can’t have a deep discussion with you about why the hell everyone loved the Banshees of Inisherin.

Waze uses AI to calculate the quickest real-time route from point A to B. But it doesn’t know which route is the scenic one, or which stresses you out more, or which one goes right past the apartment you shared with your ex.

Narrow AI does one job, and it does it well. Eventually, we can broaden the scope and make it even more powerful, moving in the direction of “artificial general intelligence” (AGI). But for now, by removing passengers from the equation, using a smaller vehicle, and narrowing their focus to delivery – Nuro is dramatically simplifying the problem. Starting smaller leads to quicker wins, which in my opinion means more momentum and more winning.

Bet #2 – Making decisions that prioritize long-term advantage

Many other self-driving projects are more short-term focused, making decisions that could cripple them (or at least limit their strategic options). As one example, it’s very popular to retrofit traditional passenger vehicles for autonomous vehicle testing. You’ll see Zoox-branded Toyotas in Seattle, Cruise-branded Chevys in San Francisco, and Waymo-branded Chrysler minivans (!?) in Phoenix. But those cars just look like cars, albeit with crazy racks of sensors bolted onto them. Nuro is taking a different approach, constructing their own vehicles to embrace the minimalist dimensions they’re after. By having hardware be an internal function, they can save costs and more tightly monitor quality. They’re also working on those difficult vehicle manufacturing problems sooner rather than later (cough, Tesla) …alongside the very difficult self-driving problem.

To add to the argument for why this is a good thing, they’ve vertically integrated to manufacture their own cars. BYD, a contract manufacturer, will supply the motor and battery, and cars will be built in Nuro’s new $40M factory in Nevada. That way they avoid giving other players more power than necessary in this new space. Part of how Apple maintains power is by making both the software (iOS) and hardware (iPhone). Similarly, by building their own cars, Nuro avoids the risk that someone will build a hard-to-copy, Nuro-sized car, eventually making Nuro just a self-driving software vendor.

Bet #3 – Doubling down on sensor diversity

There’s been a debate in the AV community since it began about which sensors are most important. Many AV companies, including Nuro, use a broad range of sensors, including: optical cameras, thermal cameras, lidar, and radar. They’re all good at different things. Optical cameras are cheap and help cars recognize and classify objects. Thermal cameras augment detection of pedestrians and people. Lidar uses lasers to measure distances to objects. Radar does the same but with radio waves. So while Nuro smashes together data from these sensors to chart a course on the road, Tesla is the spokesperson for the other side of the argument. They don’t believe in using lidar on AVs, and part of the reason is cost-focused. Cameras and radar are cheap, but a new Velodyne lidar sensor costs a jaw-dropping $75K. As another piece of the argument, Elon doesn’t think they’re necessary to achieve self-driving. He advocates for trusting cameras and advances in AI image recognition to solve for depth perception and obstacle detection.

Intuitively, I believe having more “senses” makes you more aware of your surroundings, so I just can’t side with Elon. Data suggests that depth perception is much better with lidar. And yes, it costs more, but those costs will come down, just as they have for other critical digital supplies. As an example, here’s what has happened over the last few decades to semiconductor prices:

So far, these bets are paying off for Nuro, and they are (Charlie Sheen) win-ning. In September 2022, Uber signed a 10-year partnership deal for Uber Eats deliveries (more on that from TechCrunch at this link). It’s a classic win-win. Nuro gets to add another name to its list of partnerships, which already includes FedEx, Domino’s, Kroger, Chipotle, Walmart, and 7 Eleven. Uber gets to improve its margins by removing costly drivers from the delivery equation. And we all get some time back.