Google's Other Monopoly

“…Google engaged in 15 years of sustained conduct that had — and continues to have — the effect of driving out rivals, diminishing competition, inflating advertising costs, reducing revenues for news publishers and content creators, snuffing out innovation, and harming the exchange of information and ideas in the public sphere.”

Wowsa! Shots fired there by Asst. Attorney General Jonathan Kanter. What is he talking about?

He’s announcing the DOJ’s latest antitrust suit against Google. Let’s put it in business terms first.

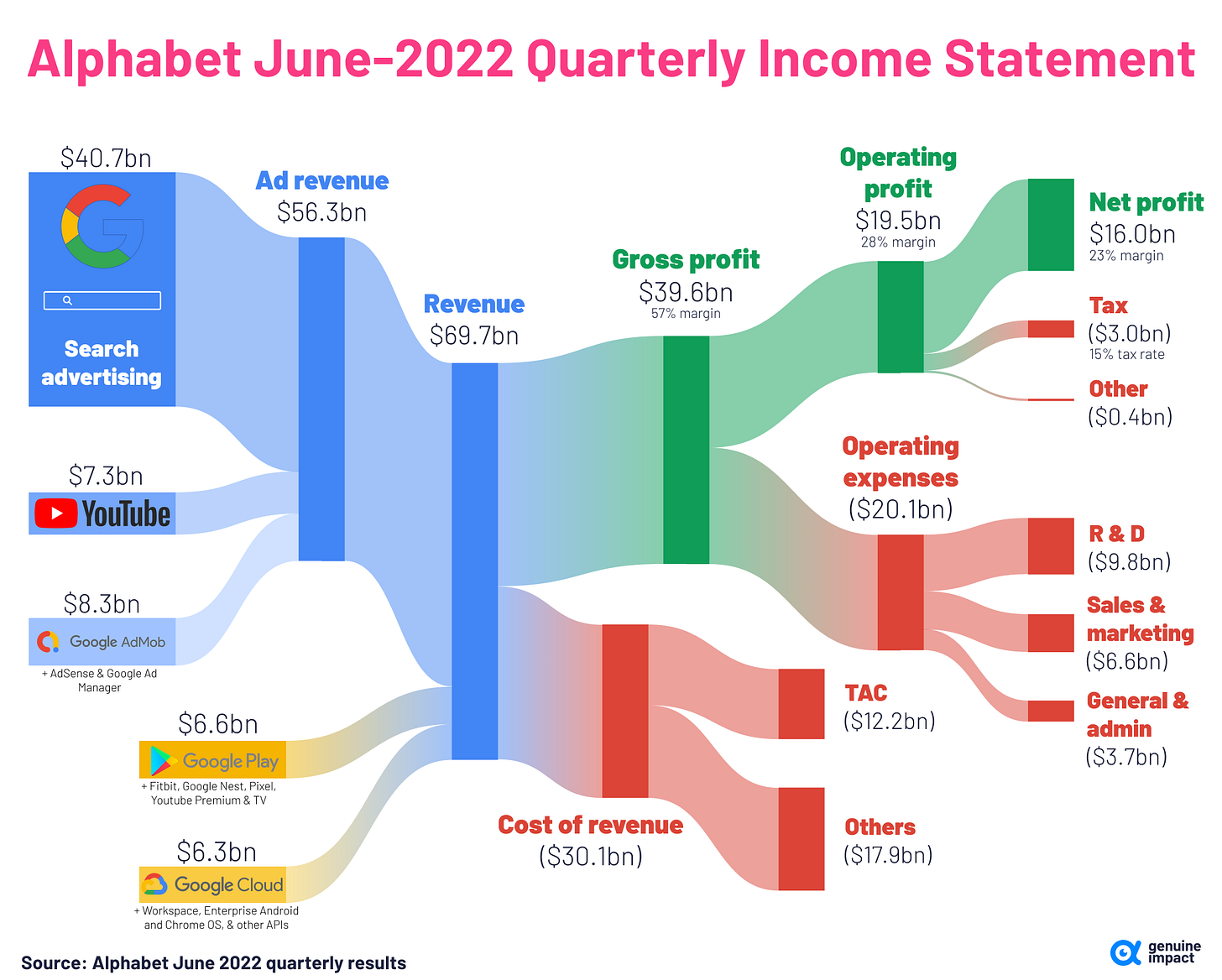

In the US digital ads space , there is ~$20B in annual revenue to publishers (i.e. Wall Street Journal, Twitter) . It comes from displaying more than 5 trillion digital ads – 13 billion per day! For Google globally, being the goliath of digital ads means $33.7B in revenue per year. This is 10%+ of their total revenue. Here’s a visual of their June 2022 quarterly results, where you can see how the pieces fit together for Google (note: stats above are annual and visual is quarterly).

You might be saying, what about Google’s search business? Isn’t that also an ads business and a monopoly? Why yes it is, you clever SOB – and that’s actually the focus of a different lawsuit from the DOJ. But as I’ll explain, I think they are intertwined.

To round out the answer on what we’re even talking about with the digital ads business (“Google AdMob” in the visual), let’s go to school.

AdTech 101

Believe it or not, most digital ads you see are the result of an instantaneous auction. In the auction, a publisher takes bids from multiple advertisers, and the winner gets to display their ad. Crazily, this happens for each and every person, every single time they open a web page with ads.

Now as you might imagine, this is a technically difficult thing to do. It requires moving lightning fast. It also requires a sophisticated set of tools.

Publishers, who own the real estate for the ads, need tools to help them:

Serve ads – take the ad from the winning bid and display it

Manage inventory – how much ad space is available, on which pages

Enable new ad formats – banner vs side scroller vs horrible mini-video-popup

Advertisers, on the other hand, need tools to help them:

Target effectively – taking user data from publishers so that ads are relevant to them

Manage campaigns – setting advertising budgets, allocating spend across various ad types

Analyze performance – understand what’s working (i.e. are people clicking?!)

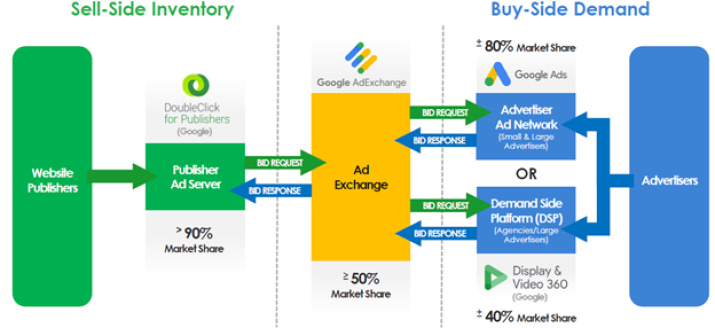

I’m over-simplifying a bit here, but as a result of the different needs, the modern “adtech stack” has three key pieces:

Supply side platform (SSP) – this is the publishers’ tool

Demand side platform (DSP) – this is the advertisers’ tool

Ad exchange – this is where the magic happens in the middle

DOJ’s Case

The core reason the DOJ is calling Google ugly names is that Google provides the dominant tool for all three pieces! Check this out – and look at the market share for each piece:

(Note: Google Ads is for smaller advertisers, and Display & Video 360 is for larger advertisers, but they are both Google-controlled DSP’s)

In the mind of the DOJ, it’s not just that Google dominates… they argue that for 15 years Google has behaved anticompetitively because they:

Acquired competitors – maximizing their control of the stack and stamping-out threats

Prioritized Google’s exchange – designing the system to give Google “first dibs”

Manually manipulated auctions – over/under-bidding to help Google or hurt competitors

Let’s look at real stories to see how these strategies worked together.

Storytime

Google struck gold in 2000. That’s the year they launched AdWords (now Google Ads), where businesses could buy ads shown right alongside Google search results. Today, that business is a cash volcano – it brought in revenues of $162B in 2022 (57% of total revenue).

A few years after AdWords launched, they realized it would be awesome (and not too hard) to help those advertisers buy ads on non-Google sites, so they built that out. When that went well, they launched their own publisher ad server. But that didn’t go so well. They struggled to get traction with their own ad server, so in 2008 they bought DoubleClick (now called DoubleClick for Publishers or DFP), which had 60% market share at the time. Later that year, they bought AdX, a new(ish) ad exchange.

Reflection time: Let’s pause here for a second. So far, I think all of this is OK. They are building things customers want, they’re bringing structure and pushing modern tech into an industry that used to have Don Drapers running around… Things are good at this point. Also, it’s worth noting that the FTC (can review all M&A – learn more in “FTC 101”) reviewed the DoubleClick acquisition and voted 4-to-1 in favor of it. Smooth sailing.

Now they had three key adtech tools, but AdWords was much stronger than the other two. Time to hit the gym.

First, they created special AdWords campaigns that could only be accessed by Publishers using DFP and AdX. It’s like McDonalds bringing back the McRib, but you can’t just get the sandwich… you have to get the XL combo and a McFlurry (pretend the machine isn’t always broken…). You get what I’m saying. This boosted demand for AdX and DFP. Second, Google boosted publisher revenue by configuring Google Ads to overbid. So advertisers paid more for the same stuff, publishers saw a revenue boost, and more publishers chose to move to DFP. Third, Google gave AdX first dibs on anything from DFP, so AdX wasn’t really a neutral marketplace. Instead, it enjoyed the equivalent of home court advantage – better access and better outcomes. Wow.

Reflection time: It’s hard to draw a definitive line, but for me this is where things start to be “not cool, man”. The first strategy is fine – if customers don’t want the McRib combo, they can just get something else or go to Wendy’s. The second strategy is harder to untangle, and it’s possible that even though advertisers paid more, they might have gotten other benefits. But the third strategy is pretty ridiculous – an exchange/marketplace should be neutral.

Over time, many competitors to Google’s adtech products were pushed out – forced to close or redirect to adjacent businesses. And new entrants were rare. For example, according to the DOJ, no new ad servers have entered the market since Google bought DoubleClick back in 2008, so DFP now has 90%+ market share. And Google has aggressively defended any threat, including new innovations customers wanted. Two specific examples:

“Yield managers” were tools to help publishers price shop, comparing AdX prices to those of other exchanges to maximize revenue, and the leading yield manager was called AdMeld. Google bought AdMeld in 2011 and promptly turned off any comparisons outside of Google’s ecosystem.

“Header bidding”, which let non-Google exchanges bid for premium publisher space before handing-off to AdX. This gave publishers more control, and it boosted their revenues by 30-40%. In response, Google manipulated the markets to try to “starve” publishers embracing header bidding.

What Happens Next

The DOJ wants Google to unwind its acquisitions of DoubleClick and AdX, selling them and only keeping control of the DSPs (DV 360 and Google Ads). It also wants to be paid damages! They have advertised using Google’s products, and they argue they’ve overpaid as a result of the Google strategies described above.

In my opinion – Google should settle the case and do what DOJ is asking. Here’s why:

The evidence is compelling. I’m no lawyer, but Google’s “tilting” of the AdX exchange – to preference themselves or to hurt rival companies – is pretty damning. According to CNBC, legal experts also find the evidence compelling, even if it’s not a slam dunk case.

They keep advertisers close. Of the three businesses, this seems the most strategically important. Advertisers are spending money to be on 3rd party sites AND on all of Google’s properties (YouTube, Google search, etc.). Therefore, keeping them close is important.

Regulatory pressure is already high. I would argue it’s never been higher. There’s another DOJ case targeting Google’s search business, plus a new EU bill regulating tech giants, plus the threat of a similar bill in the US. It seems smart to limit the number of regulatory battles you’re fighting, and possibly even generate some goodwill with one of the “adversaries”.

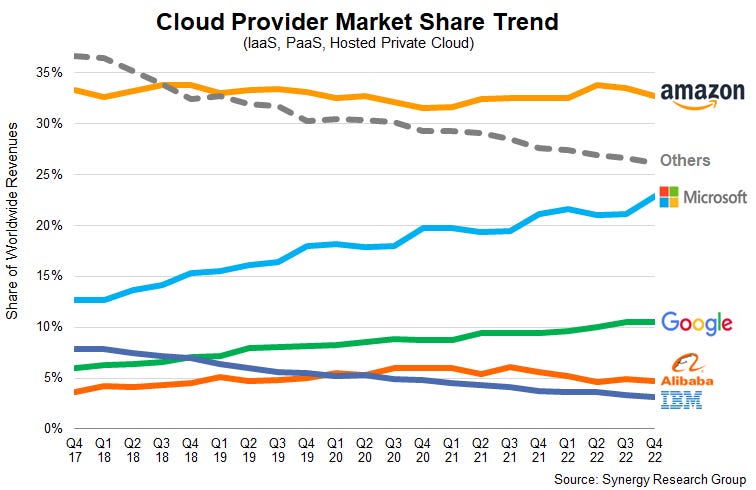

Business pressure is also very high. In search, pressure comes from Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI to build GPT into its Bing search. In Cloud, Microsoft is again powering ahead while Google stays mostly flat (see graph below). Fighting multiple battles is a distraction to management, and they need all the focus they can muster to fend off these competitive threats.

The spinoffs would be lucrative. They would still get paid for the sales and/or get equity in the new companies. For example, when Ebay spun Paypal, each Ebay shareholder was given one Paypal share per Ebay share they owned.

They can live without the extra ongoing revenue. The 3-pack-combo contributes 10%, which is a meaningful chunk of business, but it’s not catastrophic to lose it. Plus they won’t lose the full 10% -- they get to keep the DSP’s (granted we don’t have visibility into what % of revenue that is).

Now let’s be honest – I predict that they won’t follow my advice. I think they’ll slow roll this case the same way they have with the Search case (launched by DOJ in 2020, finally going to trial in September 2023).

But it would be nice if this was like the Monopoly board game – we acknowledge they “won”, and they hit reset so the game can be fairer moving forward.